R Basics continued - factors and data frames

Klaus Schliep

Mai 17, 2021

03-basics-factors-dataframes.RmdWorking with spreadsheets (tabular data)

A substantial amount of the data we work with in genomics will be tabular data, this is data arranged in rows and columns - also known as spreadsheets. We could write a whole lesson on how to work with spreadsheets effectively (actually we did). For our purposes, we want to remind you of a few principles before we work with our first set of example data:

1) Keep raw data separate from analyzed data

This is principle number one because if you can’t tell which files are the original raw data, you risk making some serious mistakes (e.g. drawing conclusion from data which have been manipulated in some unknown way).

2) Keep spreadsheet data Tidy

The simplest principle of Tidy data is that we have one row in our spreadsheet for each observation or sample, and one column for every variable that we measure or report on. As simple as this sounds, it’s very easily violated. Most data scientists agree that significant amounts of their time is spent tidying data for analysis. Read more about data organization in our lesson and in this paper.

3) Trust but verify

Finally, while you don’t need to be paranoid about data, you should have a plan for how you will prepare it for analysis. This a focus of this lesson. You probably already have a lot of intuition, expectations, assumptions about your data - the range of values you expect, how many values should have been recorded, etc. Of course, as the data get larger our human ability to keep track will start to fail (and yes, it can fail for small data sets too). R will help you to examine your data so that you can have greater confidence in your analysis, and its reproducibility.

Tip: Keeping you raw data separate

When you work with data in R, you are not changing the original file you loaded that data from. This is different than (for example) working with a spreadsheet program where changing the value of the cell leaves you one “save”-click away from overwriting the original file. You have to purposely use a writing function (e.g.

write.csv()) to save data loaded into R. In that case, be sure to save the manipulated data into a new file. More on this later in the lesson.

Importing tabular data into R

There are several ways to import data into R. For our purpose here, we will focus on using the tools every R installation comes with (so called “base” R) to import a comma-delimited file containing the results of our variant calling workflow. We will need to load the sheet using a function called read.csv().

Exercise: Review the arguments of the

read.csv()functionBefore using the

read.csv()function, use R’s help feature to answer the following questions.Hint: Entering ‘?’ before the function name and then running that line will bring up the help documentation. Also, when reading this particular help be careful to pay attention to the ‘read.csv’ expression under the ‘Usage’ heading. Other answers will be in the ‘Arguments’ heading.

What is the default parameter for ‘header’ in the

read.csv()function?What argument would you have to change to read a file that was delimited by semicolons (;) rather than commas?

What argument would you have to change to read file in which numbers used commas for decimal separation (i.e. 1,00)?

What argument would you have to change to read in only the first 10,000 rows of a very large file?

Now, let’s read in the file combined_tidy_vcf.csv which will be located in https://github.com/KlausVigo/Metagenomics/tree/master/vignettes/combined_tidy_vcf.csv. Call this data variants. The first argument to pass to our read.csv() function is the file path for our data. The file path must be in quotes and now is a good time to remember to use tab autocompletion. If you use tab autocompletion you avoid typos and errors in file paths. Use it!

## read in a CSV file and save it as 'variants'

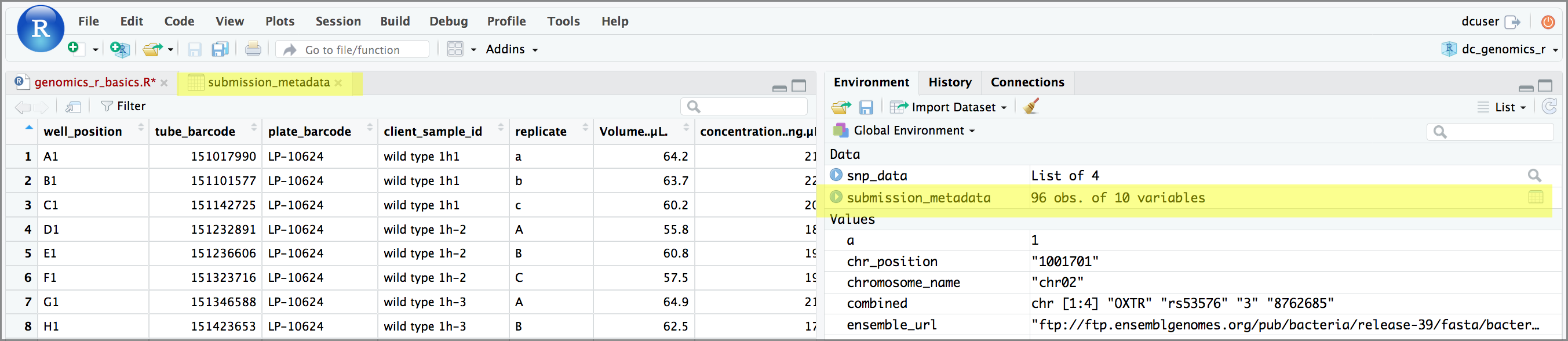

variants <- read.csv("combined_tidy_vcf.csv")One of the first things you should notice is that in the Environment window, you have the variants object, listed as 801 obs. (observations/rows) of 29 variables (columns). Double-clicking on the name of the object will open a view of the data in a new tab.

Summarizing and determining the structure of a data frame.

A data frame is the standard way in R to store tabular data. A data fame could also be thought of as a collection of vectors, all of which have the same length. Using only two functions, we can learn a lot about out data frame including some summary statistics as well as well as the “structure” of the data frame. Let’s examine what each of these functions can tell us:

## get summary statistics on a data frame

summary(variants)## sample_id CHROM POS ID

## Length:801 Length:801 Min. : 1521 Mode:logical

## Class :character Class :character 1st Qu.:1115970 NA's:801

## Mode :character Mode :character Median :2290361

## Mean :2243682

## 3rd Qu.:3317082

## Max. :4629225

##

## REF ALT QUAL FILTER

## Length:801 Length:801 Min. : 4.385 Mode:logical

## Class :character Class :character 1st Qu.:139.000 NA's:801

## Mode :character Mode :character Median :195.000

## Mean :172.276

## 3rd Qu.:225.000

## Max. :228.000

##

## INDEL IDV IMF DP

## Mode :logical Min. : 2.000 Min. :0.5714 Min. : 2.00

## FALSE:700 1st Qu.: 7.000 1st Qu.:0.8824 1st Qu.: 7.00

## TRUE :101 Median : 9.000 Median :1.0000 Median :10.00

## Mean : 9.396 Mean :0.9219 Mean :10.57

## 3rd Qu.:11.000 3rd Qu.:1.0000 3rd Qu.:13.00

## Max. :20.000 Max. :1.0000 Max. :79.00

## NA's :700 NA's :700

## VDB RPB MQB BQB

## Min. :0.0005387 Min. :0.0000 Min. :0.0000 Min. :0.1153

## 1st Qu.:0.2180410 1st Qu.:0.3776 1st Qu.:0.1070 1st Qu.:0.6963

## Median :0.4827410 Median :0.8663 Median :0.2872 Median :0.8615

## Mean :0.4926291 Mean :0.6970 Mean :0.5330 Mean :0.7784

## 3rd Qu.:0.7598940 3rd Qu.:1.0000 3rd Qu.:1.0000 3rd Qu.:1.0000

## Max. :0.9997130 Max. :1.0000 Max. :1.0000 Max. :1.0000

## NA's :773 NA's :773 NA's :773

## MQSB SGB MQ0F ICB

## Min. :0.01348 Min. :-0.6931 Min. :0.00000 Mode:logical

## 1st Qu.:0.95494 1st Qu.:-0.6762 1st Qu.:0.00000 NA's:801

## Median :1.00000 Median :-0.6620 Median :0.00000

## Mean :0.96428 Mean :-0.6444 Mean :0.01127

## 3rd Qu.:1.00000 3rd Qu.:-0.6364 3rd Qu.:0.00000

## Max. :1.01283 Max. :-0.4536 Max. :0.66667

## NA's :48

## HOB AC AN DP4 MQ

## Mode:logical Min. :1 Min. :1 Length:801 Min. :10.00

## NA's:801 1st Qu.:1 1st Qu.:1 Class :character 1st Qu.:60.00

## Median :1 Median :1 Mode :character Median :60.00

## Mean :1 Mean :1 Mean :58.19

## 3rd Qu.:1 3rd Qu.:1 3rd Qu.:60.00

## Max. :1 Max. :1 Max. :60.00

##

## Indiv gt_PL gt_GT gt_GT_alleles

## Length:801 Length:801 Min. :1 Length:801

## Class :character Class :character 1st Qu.:1 Class :character

## Mode :character Mode :character Median :1 Mode :character

## Mean :1

## 3rd Qu.:1

## Max. :1

## Our data frame had 29 variables, so we get 29 fields that summarize the data. The QUAL, IMF, and VDB variables (and several others) are numerical data and so you get summary statistics on the min and max values for these columns, as well as mean, median, and interquartile ranges. Many of the other variables (e.g. sample_id) are treated as categorical data (which have special treatment in R - more on this in a bit). The most frequent 6 different categories and the number of times they appear (e.g. the sample_id called ‘SRR2584863’ appeared 25 times) are displayed. There was only one value for CHROM, “CP000819.1” which appeared in all 801 observations.

Before we operate on the data, we also need to know a little more about the data frame structure to do that we use the str() function:

## get the structure of a data frame

str(variants)## 'data.frame': 801 obs. of 29 variables:

## $ sample_id : chr "SRR2584863" "SRR2584863" "SRR2584863" "SRR2584863" ...

## $ CHROM : chr "CP000819.1" "CP000819.1" "CP000819.1" "CP000819.1" ...

## $ POS : int 9972 263235 281923 433359 473901 648692 1331794 1733343 2103887 2333538 ...

## $ ID : logi NA NA NA NA NA NA ...

## $ REF : chr "T" "G" "G" "CTTTTTTT" ...

## $ ALT : chr "G" "T" "T" "CTTTTTTTT" ...

## $ QUAL : num 91 85 217 64 228 210 178 225 56 167 ...

## $ FILTER : logi NA NA NA NA NA NA ...

## $ INDEL : logi FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE ...

## $ IDV : int NA NA NA 12 9 NA NA NA 2 7 ...

## $ IMF : num NA NA NA 1 0.9 ...

## $ DP : int 4 6 10 12 10 10 8 11 3 7 ...

## $ VDB : num 0.0257 0.0961 0.7741 0.4777 0.6595 ...

## $ RPB : num NA 1 NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA ...

## $ MQB : num NA 1 NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA ...

## $ BQB : num NA 1 NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA ...

## $ MQSB : num NA NA 0.975 1 0.916 ...

## $ SGB : num -0.556 -0.591 -0.662 -0.676 -0.662 ...

## $ MQ0F : num 0 0.167 0 0 0 ...

## $ ICB : logi NA NA NA NA NA NA ...

## $ HOB : logi NA NA NA NA NA NA ...

## $ AC : int 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 ...

## $ AN : int 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 ...

## $ DP4 : chr "0,0,0,4" "0,1,0,5" "0,0,4,5" "0,1,3,8" ...

## $ MQ : int 60 33 60 60 60 60 60 60 60 60 ...

## $ Indiv : chr "/home/dcuser/dc_workshop/results/bam/SRR2584863.aligned.sorted.bam" "/home/dcuser/dc_workshop/results/bam/SRR2584863.aligned.sorted.bam" "/home/dcuser/dc_workshop/results/bam/SRR2584863.aligned.sorted.bam" "/home/dcuser/dc_workshop/results/bam/SRR2584863.aligned.sorted.bam" ...

## $ gt_PL : chr "121,0" "112,0" "247,0" "91,0" ...

## $ gt_GT : int 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 ...

## $ gt_GT_alleles: chr "G" "T" "T" "CTTTTTTTT" ...Ok, thats a lot up unpack! Some things to notice.

- the object type

data.frameis displayed in the first row along with its dimensions, in this case 801 observations (rows) and 29 variables (columns) - Each variable (column) has a name (e.g.

sample_id). This is followed by the object mode (e.g. factor, int, num, etc.). Notice that before each variable name there is a$- this will be important later.

Introducing Factors

Factors are the final major data structure we will introduce in our R genomics lessons. Factors can be thought of as vectors which are specialized for categorical data. Given R’s specialization for statistics, this make sense since categorial and continuous variables usually have different treatments. Sometimes you may want to have data treated as a factor, but in other cases, this may be undesirable.

Since some of the data in our data frame are factors, lets see how factors work. First, we’ll extract one of the columns of our data frame to a new object, so that we don’t end up modifying the variants object by mistake.

## extract the "REF" column to a new object

REF <- variants$REFLet’s look at the first few items in our factor using head():

head(REF)## [1] "T" "G" "G" "CTTTTTTT" "CCGC" "C"What we get back are the items in our factor, and also something called “Levels”. Levels are the different categories contained in a factor. By default, R will organize the levels in a factor in alphabetical order. So the first level in this factor is “A”.

Lets look at the contents of a factor in a slightly different way using str():

str(REF)## chr [1:801] "T" "G" "G" "CTTTTTTT" "CCGC" "C" "C" "G" ...For the sake of efficiency, R stores the content of a factor as a vector of integers, which an integer is assigned to each of the possible levels. Recall levels are assigned in alphabetical order. In this case, the first item in our “REF” object is “T”, which happens to be the 49th level of our factor, ordered alphabeticaly. The next two items are both “G”s, which is the 33rd level of our factor.

Plotting and ordering factors

One of the most common uses for factors will be when you plot categorical values. For example, suppose we want to know how many of our variants had each possible nucleotide (or nucleotide combination) in the reference genome? We could generate a plot:

#plot(REF)This isn’t a particularly pretty example of a plot. We’ll be learning much more about creating nice, publication-quality graphics later in this lesson.

Subsetting data frames

Next, we are going to talk about how you can get specific values from data frames, and where necessary, change the mode of a column of values.

The first thing to remember is that a data frame is two-dimensional (rows and columns). Therefore, to select a specific value we will will once again use [] (bracket) notation, but we will specify more than one value (except in some cases where we are taking a range).

Exercise: Subsetting a data frame

Try the following indices and functions and try to figure out what they return

variants[1,1]

variants[2,4]

variants[801,29]

variants[2, ]

variants[-1, ]

variants[1:4,1]

variants[1:10,c("REF","ALT")]

variants[,c("sample_id")]

variants$sample_id

variants[variants$REF == "A",]

The subsetting notation is very similar to what we learned for vectors. The key differences include:

- Typically provide two values separated by commas: data.frame[row, column]

- In cases where you are taking a continuous range of numbers use a colon between the numbers (start:stop, inclusive)

- For a non continuous set of numbers, pass a vector using

c() - Index using the name of a column(s) by passing them as vectors using

c()

Finally, in all of the subsetting exercises above, we printed values to the screen. You can create a new data frame object by assigning them to a new object name:

# create a new data frame containing only observations from SRR2584863

SRR2584863_variants <- variants[variants$sample_id == "SRR2584863",]

# check the dimension of the data frame

dim(SRR2584863_variants)## [1] 25 29

# get a summary of the data frame

summary(SRR2584863_variants)## sample_id CHROM POS ID

## Length:25 Length:25 Min. : 9972 Mode:logical

## Class :character Class :character 1st Qu.:1331794 NA's:25

## Mode :character Mode :character Median :2618472

## Mean :2464989

## 3rd Qu.:3488669

## Max. :4616538

##

## REF ALT QUAL FILTER

## Length:25 Length:25 Min. : 31.89 Mode:logical

## Class :character Class :character 1st Qu.:104.00 NA's:25

## Mode :character Mode :character Median :211.00

## Mean :172.97

## 3rd Qu.:225.00

## Max. :228.00

##

## INDEL IDV IMF DP

## Mode :logical Min. : 2.00 Min. :0.6667 Min. : 2.0

## FALSE:19 1st Qu.: 3.25 1st Qu.:0.9250 1st Qu.: 9.0

## TRUE :6 Median : 8.00 Median :1.0000 Median :10.0

## Mean : 7.00 Mean :0.9278 Mean :10.4

## 3rd Qu.: 9.75 3rd Qu.:1.0000 3rd Qu.:12.0

## Max. :12.00 Max. :1.0000 Max. :20.0

## NA's :19 NA's :19

## VDB RPB MQB BQB

## Min. :0.01627 Min. :0.9008 Min. :0.04979 Min. :0.7507

## 1st Qu.:0.07140 1st Qu.:0.9275 1st Qu.:0.09996 1st Qu.:0.7627

## Median :0.37674 Median :0.9542 Median :0.15013 Median :0.7748

## Mean :0.40429 Mean :0.9517 Mean :0.39997 Mean :0.8418

## 3rd Qu.:0.65951 3rd Qu.:0.9771 3rd Qu.:0.57507 3rd Qu.:0.8874

## Max. :0.99604 Max. :1.0000 Max. :1.00000 Max. :1.0000

## NA's :22 NA's :22 NA's :22

## MQSB SGB MQ0F ICB

## Min. :0.5000 Min. :-0.6904 Min. :0.00000 Mode:logical

## 1st Qu.:0.9599 1st Qu.:-0.6762 1st Qu.:0.00000 NA's:25

## Median :0.9962 Median :-0.6620 Median :0.00000

## Mean :0.9442 Mean :-0.6341 Mean :0.04667

## 3rd Qu.:1.0000 3rd Qu.:-0.6168 3rd Qu.:0.00000

## Max. :1.0128 Max. :-0.4536 Max. :0.66667

## NA's :3

## HOB AC AN DP4 MQ

## Mode:logical Min. :1 Min. :1 Length:25 Min. :10.00

## NA's:25 1st Qu.:1 1st Qu.:1 Class :character 1st Qu.:60.00

## Median :1 Median :1 Mode :character Median :60.00

## Mean :1 Mean :1 Mean :55.52

## 3rd Qu.:1 3rd Qu.:1 3rd Qu.:60.00

## Max. :1 Max. :1 Max. :60.00

##

## Indiv gt_PL gt_GT gt_GT_alleles

## Length:25 Length:25 Min. :1 Length:25

## Class :character Class :character 1st Qu.:1 Class :character

## Mode :character Mode :character Median :1 Mode :character

## Mean :1

## 3rd Qu.:1

## Max. :1

## Coercing values in data frames

Tip: coercion isn’t limited to data frames

While we are going to address coercion in the context of data frames most of these methods apply to other data structures, such as vectors

Sometimes, it is possible that R will misinterpret the type of data represented in a data frame, or store that data in a mode which prevents you from operating on the data the way you wish. For example, a long list of gene names isn’t usually thought of as a categorical variable, the way that your experimental condition (e.g. control, treatment) might be. More importantly, some R packages you use to analyze your data may expect characters as input, not factors. At other times (such as plotting or some statistical analyses) a factor may be more appropriate. Ultimately, you should know how to change the mode of an object.

First, its very important to recognize that coercion happens in R all the time. This can be a good thing when R gets it right, or a bad thing when the result is not what you expect. Consider:

## [1] "character"Although there are several numbers in our vector, they are all in quotes, so we have explicitly told R to consider them as characters. However, even if we removed the quotes from the numbers, R would coerce everything into a character:

## [1] "character"

snp_chromosomes_2[1]## [1] "3"We can use the as. functions to explicitly coerce values from one form into another. Consider the following vector of characters, which all happen to be valid numbers:

## [1] "character"

snp_positions_2[1]## [1] "8762685"Now we can coerce snp_positions_2 into a numeric type using as.numeric():

snp_positions_2 <- as.numeric(snp_positions_2)

typeof(snp_positions_2)## [1] "double"

snp_positions_2[1]## [1] 8762685Sometimes coercion is straight forward, but what would happen if we tried using as.numeric() on snp_chromosomes_2

snp_chromosomes_2 <- as.numeric(snp_chromosomes_2)## Warning: NAs durch Umwandlung erzeugtIf we check, we will see that an NA value (R’s default value for missing data) has been introduced.

snp_chromosomes_2## [1] 3 11 NA 6Trouble can really start when we try to coerce a factor. For example, when we try to coerce the sample_id column in our data frame into a numeric mode look at the result:

as.numeric(variants$sample_id)## Warning: NAs durch Umwandlung erzeugt## [1] NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

## [26] NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

## [51] NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

## [76] NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

## [101] NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

## [126] NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

## [151] NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

## [176] NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

## [201] NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

## [226] NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

## [251] NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

## [276] NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

## [301] NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

## [326] NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

## [351] NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

## [376] NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

## [401] NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

## [426] NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

## [451] NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

## [476] NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

## [501] NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

## [526] NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

## [551] NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

## [576] NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

## [601] NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

## [626] NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

## [651] NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

## [676] NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

## [701] NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

## [726] NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

## [751] NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

## [776] NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA

## [801] NAStrangely, it works! Almost. Instead of giving an error message, R returns numeric values, which in this case are the integers assigned to the levels in this factor. This kind of behavior can lead to hard-to-find bugs, for example when we do have numbers in a factor, and we get numbers from a coercion. If we don’t look carefully, we may not notice a problem.

If you need to coerce an entire column you can overwrite it using an expression like this one:

# make the 'REF' column a character type column

variants$REF <- as.character(variants$REF)

# check the type of the column

typeof(variants$REF)## [1] "character"StringsAsFactors = FALSE

Lets summarize this section on coercion with a few take home messages.

- When you explicitly coerce one data type into another (this is known as explicit coercion), be careful to check the result. Ideally, you should try to see if its possible to avoid steps in your analysis that force you to coerce.

- R will sometimes coerce without you asking for it. This is called (appropriately) implicit coercion. For example when we tried to create a vector with multiple data types, R chose one type through implicit coercion.

- Check the structure (

str()) of your data frames before working with them!

Regarding the first bullet point, one way to avoid needless coercion when importing a data frame using any one of the read.table() functions such as read.csv() is to set the argument StringsAsFactors to FALSE. By default, this argument is TRUE. Setting it to FALSE will treat any non-numeric column to a character type. read.csv() documentation, you will also see you can explicitly type your columns using the colClasses argument. Other R packages (such as the Tidyverse “readr”) don’t have this particular conversion issue, but many packages will still try to guess a data type.

Data frame bonus material: math, sorting, renaming

Here are a few operations that don’t need much explanation, but which are good to know.

There are lots of arithmetic functions you may want to apply to your data frame, covering those would be a course in itself (there is some starting material here). Our lessons will cover some additional summary statistical functions in a subsequent lesson, but overall we will focus on data cleaning and visualization.

You can use functions like mean(), min(), max() on an individual column. Let’s look at the “DP” or filtered depth. This value shows the number of filtered reads that support each of the reported variants.

max(variants$DP)## [1] 79You can sort a data frame using the order() function:

## [1] 2 2 2 2 2 2Exercise

The

order()function lists values in increasing order by default. Look at the documentation for this function and changesorted_by_DPto start with variants with the greatest filtered depth (“DP”).

You can rename columns:

colnames(variants)[colnames(variants) == "sample_id"] <- "strain"

# check the column name (hint names are returned as a vector)

colnames(variants)## [1] "strain" "CHROM" "POS" "ID"

## [5] "REF" "ALT" "QUAL" "FILTER"

## [9] "INDEL" "IDV" "IMF" "DP"

## [13] "VDB" "RPB" "MQB" "BQB"

## [17] "MQSB" "SGB" "MQ0F" "ICB"

## [21] "HOB" "AC" "AN" "DP4"

## [25] "MQ" "Indiv" "gt_PL" "gt_GT"

## [29] "gt_GT_alleles"Saving your data frame to a file

We can save data to a file. We will save our SRR2584863_variants object to a .csv file using the write.csv() function:

write.csv(SRR2584863_variants, file = "SRR2584863_variants.csv")The write.csv() function has some additional arguments listed in the help, but at a minimum you need to tell it what data frame to write to file, and give a path to a file name in quotes (if you only provide a file name, the file will be written in the current working directory).